There’s magic in the sound of a Hammond B-3: there is also some deep, old-school technology. Like many of the core techniques used in electronic music, the tone wheels at this instrument’s heart spring in part from ideas developed for far more “serious” inventions, including one created by an associate of Albert Einstein.

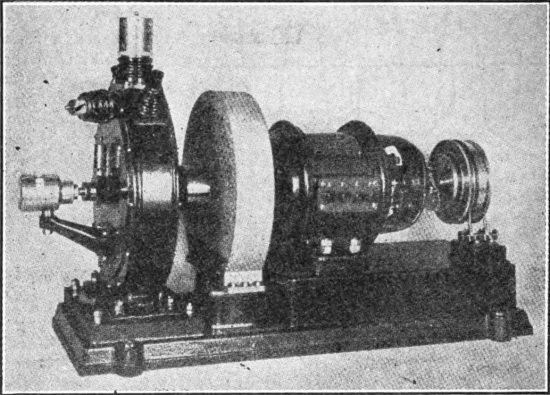

While in the 1890s Thaddeus Cahill’s Telharmonium relied on sound generating technology often now referred to as “tone wheels,” they were actually large dynamo rotor shafts that greatly contributed to the Telharmonium’s weight of 200 tons. His 1897 patent application only uses the word “wheel” once, in a section describing techniques his invention does not use.

A tone wheel featured prominently in an invention by the German engineer Rudolf Goldschmidt in 1910. He was working in the field of high-power intercontinental radiotelegraphy and had already invented the Goldschmidt alternator, a radio-frequency alternating current generator that could be used as a radio transmitter. For his radiotelegraphy solution to be practical however Goldschmidt needed another invention.

Unlike the familiar click of the traditional telegraph, radiotelegraphy creates “dots” and “dashes” frequencies much higher than the human ear can hear. Since training dogs to be telegraph operators wasn’t practical, they needed to be brought down into the human audio range. Goldschmidt used a technique called heterodyning to do this and he invented a tone wheel to act as a beat frequency oscillator. If you’ve ever tuned a guitar by listening to the “beating” between strings, you’ve experienced beat frequencies.

Radiotelegraphy using the Goldschmidt alternator and tone wheel allowed the first direct, regular communication between Germany and the United States and was an important tool in the negotiations ending WWI. During the 1920s, Goldschmidt met Albert Einstein and the two of them collaborated on the design of an audio product, a hearing aid that unfortunately never went into production.

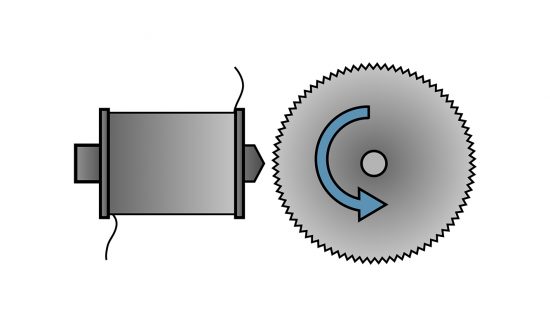

Goldschmidt’s tone wheel, while adequate for telegraphy, was probably a bit harsh for musical applications. Its output was a square wave created by making and breaking electrical contacts around the edge of the spinning wheel. Musical applications required a sweeter timbre. Simple musical tone wheels can be thought of as a combination of a vinyl record and an electric guitar pickup. Maybe that’s why they sound so good.

While a string of complex bumps in the groove of a record encode the music recorded there, on a tone wheel the bumps are moved from the surface of the vinyl disc to the outer edge of a metallic one. Since they are encoding a single note or frequency and not a whole song, tone wheel bumps are much more regular and uniform.

Instead of a phonograph needle, a device like an electro-magnetic guitar pickup is placed near the edge of the disc. When the disc is rotated, the metal bumps pass through the pickup’s magnetic field and induce an alternating current that becomes the audio output.

Musical applications of tone wheels were explored during the 1920s and early 1930s by Emile Hugoniot in France and Wilhelm Lenk and Rudolf Stelzhammer in Austria. There were no commercial successes however until 1935 when Laurens Hammond first marketed his tone wheel organs to churches as a low-cost alternative to expensive pipe organs. While they were a passable substitute, they also had a distinctive voice of their own and “organ trios” began appearing in jazz clubs. A few decades later they were a rock music staple, backing up guitarists like Eric Clapton and front-and-center in groups like Emerson, Lake and Palmer.

The iconic sound of Hammond’s flagship instrument, the B-3, is in a large part defined by things that Hammond himself felt were design defects. Organs often developed a click or pop when a key was depressed. When this was “fixed” in later instruments some players complained because they liked the more percussive attack it provided.

Tone wheel leakage or crosstalk, another common occurrence, was caused by pickups receiving stray signals from nearby wheels. Hammond added filtering to eliminate this, but musicians consider it and key click such significant components of the B-3’s character that modern “Clone Wheel” digital emulations go to great lengths to model these behaviors.

The last Hammond tone wheel organs were manufactured in 1975. Hammond organs were extremely well-engineered, and many are still in regular use. Unfortunately, the demand for this classic sound outstrips the available supply and the instruments are bulky by today’s standards. Clone wheel is a tongue-in-cheek industry name for new lighter digital instruments that simulate these classics. In an enduring testament to tone wheel technology though, this sound is now being carried into the future by scores of engineers and programmers faithfully modeling the physics of these old whirling metal discs.

Great explanation of the origin as well as the function of the “tone wheel”. Thanks.

I have an M-111 available for sale -needs a little work…

I still use a Hammond ‘D’ circa 1939. Eighty years later, and the mechanical parts are working perfectly. The internal electronics need work, but I take a signal from the volume pedal straight into a sound system and the beast works perfectly. Perfectly in tune and amazing sound after 80 years of use.

That is amazing. Our oldest is a ’57 B3. It just needs oil occasionally. Thanks John!

Had a 1936 Model A years ago. The original tremelo-style and squared keys. Wonderful, real organ, Sounded beautful, and was completely reliable!

LA Hammond technician Ken Rich told me someone had priced out what it would cost to build a Hammond B3 now… Am I knew this was 10 years ago. The answer?

60 grand.

No doubt. As we found working on motor replacement solutions, it’s not as easy as it may look to replace this old and reliable vintage technology. It was really leading edge in its day – and for decades more! Thanks Jeff.

60K is a bargain! Thorens are going to ask about a quarter of that for their reissued TD-124 turntable.